At first, the recently planted row of pepper plants appeared submerged in a sea of grass and weeds. My job was to weed the bed. I began by clearing a circle around each pepper plant, pulling out all the other plants around it until a tidy rectangle of bare soil emerged with two rows of pepper plants now clearly visible. I only got through half the bed before a summer thunderstorm quenched the ground, inspiring me to retreat to the house. My husband and I watched out the window as storm winds whipped the trees, tall grasses and pepper plants back and forth. The next morning, the pepper plants in the un-weeded section were standing upright as usual, enmeshed in their sea of grass. The peppers whose neighbors I had just removed were bent and broken by the storm.

After moments like this, I began to wonder… maybe it’s not such a good idea to kill everything but the crop plants? A more focused or devoted gardener would have prevented the peppers from becoming engulfed by removing the sprouts of grasses and unfriendly weeds much earlier in the season. However, with an acre of beds to help maintain while holding a job, it was hard to keep up! Sprout identification became a new area of interest. And I began to question the concept of everything besides the crop plants being a “weed.” What is a weed, after all?

Traditionally, we think of a weed as a plant that’s not supposed to be there. Many plants considered weeds grow in disturbed soil, which is what we create when we till and clear the ground to grow crops. After all, isn’t a weed just a very successful plant? I started to learn to identify the non-crop plants growing in our garden beds, and instead of killing everything but the crop plants began to leave the other species that would provide ground cover and beneficial companion effects.

At first, learning all these new plants seemed overwhelming. Even the best plant identification guides are often organized by flower type and color… but what if the plant in question is not flowering? I found the Wildflower Search website to be most helpful (https://www.wildflowersearch.org/) because it allows you to enter parameters like location, elevation, observation time, leaf attachment and habitat. Even if you leave out flower type or color, its database pulls up the most likely species for that set of parameters. There are smartphone apps that greatly assist plant ID, most notably iNaturalist and Leafsnap.

Of course there is no substitute for experience, and after 2 or 3 years of cultivating and observing the plants on our micro farm their family patterns began to emerge. Growing vegetables and leaf crops that we eat was a good place to start – learning the timing of planting, sprouting, and harvesting of plants that were already familiar to me helped my recognition of similarities between plants of the same family. An extremely helpful website for Ohio plant families is https://ohioplants.org/families/. Expanding this family-level pattern recognition to wetland plants was a natural extension, once I got out into the field with MBI’s ID of Common Wetland Plants class last June.

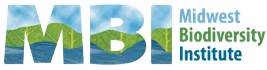

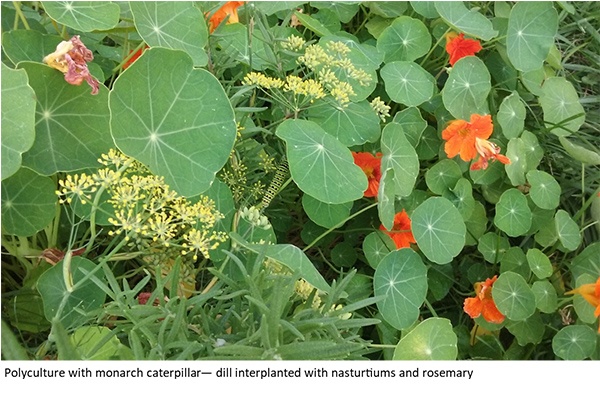

Back on the farm, as understanding of the relationships between plants increased, my thinking moved beyond the oppositional dichotomy of “weed” vs. “non-weed” or “good plant” vs. “bad plant”. How they function became more important. Some sprouts, like pokeweed, bindweed, and wild lettuce, grow into plants that tend to dominate the other plants in the garden, and these are the ones my husband and I chose to remove. Others, like ground ivy, purslane, self-heal and yarrow, grow into plants that do not occupy the same niche as the crop plants. These may provide beneficial properties to the crop such as ground cover, pollinator attraction, pest deterrence and an exchange of chemicals beneath the surface of the soil that can be mutually beneficial. As we saw the unique value of some of our “volunteers,” our garden slowly turned into more of a polyculture.

When you are able to identify sprouts and plants at times when they are not flowering, you can cultivate an area that resembles more of an ecosystem and imitates nature, rather than imposing a framework that sees only crop plants as valuable. Because plants are immobile and exist in an entirely different timescale than ours, sometimes it can be difficult to observe their unique character and the timing of their development. As animals who are especially visually oriented, it’s easy to forget that plants’ main connection to life is through their roots – through the soil, a world which is almost completely unseen to us. By the plants growing in an area, the soil is giving us clues about itself. Plants are indicators of habitat. Part of each species’ unique character is the habitat in which they prefer to grow. Plants that “volunteer” in an area, i.e. “weeds”, are telling us something about the character of that particular soil.

Because hydrophytic plant communities are one characteristic of wetlands, this principle is important when it comes to wetland delineation. Various species of plants inhabit hydric soils and indicate wetland habitat. Many wetland areas that would normally be left alone by farmers are currently plowed to grow crops due to various incentives such as subsidized crop insurance. Many times the kinds of “weeds” that pop up in agricultural fields too wet to be farmed are different from those seen in the other parts of the agricultural field. These species grow in areas that are often noticeably different from the rest of the field: the concavities or depressions that hold water. According to Professional Wetland Scientist Mick Micacchion, “given the rigorous activities - plowing, ripping, planting, fertilizer and herbicide application, and others - in the fields surrounding them, these wetlands are never intact or of high quality.”

In the same way our pepper plants that lost their neighbors were decimated by the storm, when modern agricultural fields are placed directly adjacent to wetlands, this loss of natural habitat has destructive effects on the wetland. To the wetland, the natural habitat of terrestrial plants that surrounds it acts like a buffer zone, much like the tall grasses that protected our pepper plants from the storm.

Intact wetlands “need to have intact buffers of terrestrial plant species surrounding them to limit the amount of disturbance they experience from all of the farming/agricultural activities the ag field wetlands experience,” says Micacchion. Our modern system of agriculture, although technologically advanced, still relies upon creating and maintaining a highly controlled monoculture no matter what kind of soil exists in an area. A major part of this system is regular tilling of the topsoil and the addition of chemical inputs such as nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers, herbicides and pesticides – destructive influences to adjacent wetlands.

Additionally, wetlands without a contiguous connection to Waters of the United States (WOTUS) have recently lost their federally protected status. Therefore, the job of protecting these batteries of biodiversity is left to the states. The Natural Resources Conservation Service of the USDA offers the Agricultural Conservation Easement Program to help landowners preserve and restore wetlands. Precision agriculture methods such as those supported by H2Ohio’s Water Quality Incentive Program are a step in the right direction. Alternate methods of farming, such as polyculture and permaculture, nurture soil health and could be successful on a local level. Perhaps one day, polycultures that imitate natural ecosystems will replace the machine-farmed monocultures, provide supportive neighbors for wetlands, and help protect water quality.

Steps like the ones above give our planet more resilient habitats with healthier plants and soils and cleaner water. My investigation into the health of the pepper plants on my micro farm led to a strong understanding of ecosystems and how all their components interact. To quote John Muir, “When one tugs at a single thing in nature, he finds it attached to the rest of the world.”

Image Credits

Picture 1 (Self-heal, Common Purslane and Ground Ivy)

- By Ivar Leidus - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=27062399

- By ZooFari - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8986945

- By Rasbak - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10128264

Picture 2 (Lettuce & Onions on Hugelkultur) by Emily Frechette

Picture 3 (Broadleaf Plantain, Lance-leaved Plantain, Yarrow)

- By Rasbak - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=210595

- By sannse - Originally uploaded to English Wikipedia as Ribwort 600.jpg, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=2149536

- CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=264152

Picture 4 (Polyculture with Monarch Caterpillar) by Emily Frechette

Picture 5 (Polyculture) from The Eden Project in Cornwall, England https://www.edenproject.com/

Picture 6 (Calamus Swamp big sky landscape) by Emily Frechette